It used to be the norm that in a town known for its black musical history, influence and legends, talented black musicians were hitting a sour note when it came to finding jobs in the St. Louis area. Southern Illinois University Edwardsville’s Prince Wells III, associate professor in the Department of Music and past director of the Music Business Program and the Black Studies Program at SIUE, organized, strategized and chronicled the struggles and successes of black artists. His efforts are honored as part of the #1 in Civil Rights: The African American Freedom Struggle in St. Louis exhibit at the Missouri History Museum.

It used to be the norm that in a town known for its black musical history, influence and legends, talented black musicians were hitting a sour note when it came to finding jobs in the St. Louis area. Southern Illinois University Edwardsville’s Prince Wells III, associate professor in the Department of Music and past director of the Music Business Program and the Black Studies Program at SIUE, organized, strategized and chronicled the struggles and successes of black artists. His efforts are honored as part of the #1 in Civil Rights: The African American Freedom Struggle in St. Louis exhibit at the Missouri History Museum.

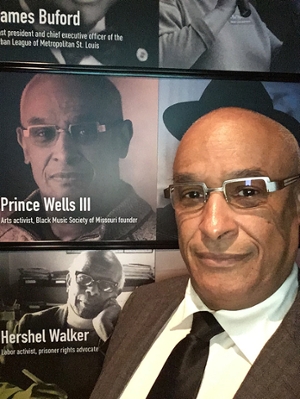

The exhibit, which shows the important role St. Louis played in the civil rights movement, opened March 17 and will end April 15, 2018. Wells is featured in “The Face of the Movement,” a wall featuring photographs of local civil rights activists. Gwen Moore, Missouri History Museum curator of urban landscape and community identity, is the curator of the exhibit.

“I was surprised to learn that I was part of the exhibit,” said Wells. “At the time, I was simply addressing issues dealing with equity and the livelihood of black musicians in the St. Louis area.

“During the height of the Jim Crow laws through the 1970s, there were few employment opportunities for black musicians except through segregated unions, and blacks were largely excluded from joining the white musician’s union,” said the trumpet player. “In short, if you were black and were trying to have a career in music in St. Louis, your opportunities were extremely limited.”

Wells has a bachelor’s in music education from SIUE and a master’s in Afro-American music and trumpet from the New England Conservatory of Music. He began teaching at SIUE in 1989.

“There were nice venues in St. Louis for musicians, such as the Fox Theatre, the American Theater and Six Flags Over Mid-America,” Wells continued. “But there were virtually no blacks playing at these locations.”

Wells tells of one specific incident as an example. The Wiz was coming to St. Louis, and he asked about job availabilities. Wells said he was told that all the musicians for the musical had already been hired. However, several days later a fellow black trumpet player told Wells that a white trumpeter had just been hired to play in the production.

It was such incidents that catapulted Wells into activism.

Wells tells of the formation of the first black musicians union in the country – Local 44. The black musician’s union, however, was revoked by the white Local 2 union between 1931-33.

According to Wells, a new black union was formed in the 1940s – Local 197. Later, in 1971, the American Federation of Musicians ordered the white local (Local 2) and the black local (Local 197) to merge due to integration. The merger took place between 1972-78 and was called Local 2-197. At the conclusion of the merger process, all black officers and board members had lost their positions. Wells joined Local 2-197 in the early 1980s.

“A group of black musicians looked at records of the official Musician Union 2-197 and found that a total of 7,318 musicians were hired over and over again,” said Wells. “Of that number, 112 were black. We filed 22 suits in federal court. We worked to change the hiring practices of such agencies as the Fox and The Muny.”

Wells also help found the non-profit group, Black Music Society in 1984. “I learned how to write grants, and we submitted a proposal to the Missouri Arts Council to conduct our own concert series,” he said. “We, as black musicians, put on the series, paid ourselves, did all the promotions and conducted the administration duties.”

Wells worked with the Black Music Society for more than 20 years.

Photo:

Prince Wells III is seen in front of his photo in the #1 in Civil Rights: The African American Freedom Struggle in St. Louis.