![Black and Blue Panel]()

From the pages of history to today’s headlines, the relationship between the African American community and the police has been an antagonistic one, according to Timothy Lewis, PhD, assistant professor in the Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Department of Political Science. Lewis, who specializes in identity politics, coordinated and moderated “Black and Blue: A Panel Discussion on Relational Policing in the African American Community.”

The discussion, held Wednesday, Feb. 19 in the Center for Student Diversity and Inclusion, featured St. Louis County Prosecutor Wesley Bell, Senior U.S. Probation Officer Demetrius Hatley, Belleville Attorney Joslyn Sandifer, and SIUE political science and philosophy major Hayley Smith.

Panel members were asked to weigh in on a series of questions. The first query was: “As a person of color, do you fear having an interaction with a police officer, such as a traffic stop. If so, why?”

“I’m a perfect case study for this question,” said Bell. “My father is a retired police officer in Atlanta, and when I went to visit him, I had no fear of being pulled over. But I grew up in St. Louis, and I did have trepidation when I got pulled over. As a young black man, I was searched and sat down on the curb while the car was being searched so much, until I thought it was normal.”

“There are a significant number of police officers who do the right thing every single day,” said Hatley. “But there is a small percentage of police officers who don’t. I’m not fearful of having an interaction with a police officer, but when I’m stopped I am concerned and my awareness goes up.

![Black and Blue Panel2]()

“I have been a federal officer for 12 years, and during that time I have been stopped 14 times. I’ve been stopped three times while on duty and 11 times on my own time. I have only been stopped by white male police officers.”

“My feelings depend on how curly I’m wearing my hair that day,” said Sandifer. “If I’m out on a Saturday and am not suited and booted, then it will color my feelings. I’m conscious of where my hands are and of my posture. If I’m coming from court, am dressed and have my hair pulled back, I feel a lot less apprehensive about the narrative of how I look.”

The speakers were also asked: “In your opinion, has social media hurt or helped relationships between African Americans and the police?”

“Social is not the crux of the problem between African Americans and the police, but the problems stem from history and people having preconceived ideas about each other,” said Smith.

“It has helped and hurt,” said Hatley. “Posting on social has forced some police agencies to change their policies and to hold officers accountable. Social media has been responsible for creating a 21st Century Policing Task Force, and some of the videos have led to the successful prosecution of bad police officers.

“At the same time, it has hurt relationships and interaction with police officers. When you see certain videos that appear that a police officer is causing harm or is disrespecting an African American, it creates an emotional reaction within you. Those reactions can make you feel like ‘I hate police officers.’”

Then Lewis asked the questions: “What are some day-to-day changes police officers can employ to improve relationships between themselves and citizens, particularly African Americans? What changes can citizens employ to improve their relationships between themselves and police officers?”

“I’m a big advocate for community policing,” responded Bell. “It is not just showing up for a school event and talking to kids. It’s about information going two ways. We have to get collective buy-in from the community. Then couple that with police getting out of their cars and talking to people. That’s when you start building trust.”

“Community policing is not anything new. Get beat cops. That’s an easy move,” remarked Sandifer. “The reality is that they used to do it in certain communities. On the other side, my suggestion is to educate yourself. Police are allowed to get demographic information from you. Know what you can and cannot do. It will make your interaction with police a little less stressful, because you will have an idea of what the interaction should look like. That will empower you.”

The final question: “A

Rutgers-Newark study shows that police use of force is a leading cause of death for black men, more so than any other race, gender or group. What is your reaction to the study?”

“It’s worrisome, but I’m not super surprised,” said Smith. “I had a 14-year-old cousin who was hauled off in a police car for having a BB gun. He was interrogated in a room, and the police would not wait for his parents to arrive. They were shocked when they heard it wasn’t a real gun. After checking it, they said he was free to go.”

“I would say it is a destructive and tragic symptom of a much larger sickness, if you will,” said Bell. “This is an American issue that needs to be addressed holistically, and not just looked at as ‘their’ problem. We need systemic, cultural change throughout society. Until we start addressing the root cause, we will just be spinning our wheels.”

“We should look at it like dealing with a plague or epidemic,” added Sandifer. “If this were high blood pressure, heart disease or cancer, we would look at it more urgently. One feeling is that black men are contributing to their own demise, as in the crack epidemic in the 1980s. But now we understand that being addicted to opioids or other drugs can create circumstances that can be out of a person’s control. We need to look at it like a healthcare problem, because it is.”

Photos:

L-R: St. Louis Prosecuting Attorney Wesley Bell and Timothy Lewis, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Political Science.

Panelists from left to right: Hayley Smith, SIUE political science and philosophy major; Joslyn Sandifer, Belleville attorney; Demetrius Hatley, senior U.S. probation officer; and Wesley Bell, St. Louis County prosecutor.

![]()

The Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Pharmacy (SOP) will engage 5th-8th grade students in discussions about prescription drug abuse, vaping and the associated dangers during “Locked in to Stay Out,” a free overnight education event from 8 p.m. Saturday, April 4 until 7:30 a.m. Sunday, April 5 in SIUE’s First Community Arena at the Vadalabene Center. Registration forms are available through Monday, March 2 at siue.edu/pharmacy/about/news/pharmacy-calendar.shtml.

The Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Pharmacy (SOP) will engage 5th-8th grade students in discussions about prescription drug abuse, vaping and the associated dangers during “Locked in to Stay Out,” a free overnight education event from 8 p.m. Saturday, April 4 until 7:30 a.m. Sunday, April 5 in SIUE’s First Community Arena at the Vadalabene Center. Registration forms are available through Monday, March 2 at siue.edu/pharmacy/about/news/pharmacy-calendar.shtml. There are no African American atheists, right? If there are, they are immoral. These counternarratives were addressed in the presentation, “Ain’t I Black too: Counternarratives of Black Atheists in College,” given by J.T. Snipes, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Educational Leadership at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, on Monday, Feb. 17 in the Center for Student Diversity and Inclusion (CSDI).

There are no African American atheists, right? If there are, they are immoral. These counternarratives were addressed in the presentation, “Ain’t I Black too: Counternarratives of Black Atheists in College,” given by J.T. Snipes, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Educational Leadership at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, on Monday, Feb. 17 in the Center for Student Diversity and Inclusion (CSDI).  College Factual’s 2020 Best Value Business Administration Schools report ranks Southern Illinois University Edwardsville’s School of Business 12th among 711 programs nationally and #1 in Illinois as “Best Value for the Money.” SIUE’s business administration program stands among the top 2% of all programs for value.

College Factual’s 2020 Best Value Business Administration Schools report ranks Southern Illinois University Edwardsville’s School of Business 12th among 711 programs nationally and #1 in Illinois as “Best Value for the Money.” SIUE’s business administration program stands among the top 2% of all programs for value. The United States Air Force Academy (USAFA) has invited Southern Illinois University Edwardsville’s Dennis Bouvier, PhD, to enrich Academy Cadets’ academic experience as a Distinguished Visiting Professor of Computer and Cyber Sciences from June 2020-May 2021.

The United States Air Force Academy (USAFA) has invited Southern Illinois University Edwardsville’s Dennis Bouvier, PhD, to enrich Academy Cadets’ academic experience as a Distinguished Visiting Professor of Computer and Cyber Sciences from June 2020-May 2021. The annual event is sponsored by Phillips 66 Wood River Refinery. It featured the Women’s Basketball team taking on Austin Peay. During timeouts, eager children participated in a marshmallow launching activity led by the SIUE STEM Center. At halftime, the Paramount Performance Pups offered a high-flying performance.

The annual event is sponsored by Phillips 66 Wood River Refinery. It featured the Women’s Basketball team taking on Austin Peay. During timeouts, eager children participated in a marshmallow launching activity led by the SIUE STEM Center. At halftime, the Paramount Performance Pups offered a high-flying performance. “This is always an exciting event for us, because it features great community engagement with our local schools,” said Chris Wright, assistant athletic director for Annual Fund and Ticketing. “For many kids, this is their first time on a college campus. We are thrilled to offer them a fun visit and hopefully inspire them to want to achieve great things like they saw today.”

“This is always an exciting event for us, because it features great community engagement with our local schools,” said Chris Wright, assistant athletic director for Annual Fund and Ticketing. “For many kids, this is their first time on a college campus. We are thrilled to offer them a fun visit and hopefully inspire them to want to achieve great things like they saw today.” East Alton Middle School, North Elementary School, Pathways School, Penniman School, Pontiac Junior High, Trimpe Middle School, and Wirth Parks Middle School.

East Alton Middle School, North Elementary School, Pathways School, Penniman School, Pontiac Junior High, Trimpe Middle School, and Wirth Parks Middle School. Great Value Colleges has selected the Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Department of Philosophy’s bachelor’s degree program as #1 in Illinois and among the nation’s Top 40 for affordability. For the complete rankings, visit

Great Value Colleges has selected the Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Department of Philosophy’s bachelor’s degree program as #1 in Illinois and among the nation’s Top 40 for affordability. For the complete rankings, visit  The rankings are determined by using data collected from College Navigator regarding tuition, as well as program information gleaned directly from each institution’s website. For more sizeable rankings, the methodology used to determine placement is based primarily on tuition. It also considers factors such as program flexibility, customization within the degree program both in content and format, and an overall “wow” factor that highlights each program’s unique offerings and sets it apart from the pack. For programs that have limited online availability, institutions are ranked based solely on tuition cost.

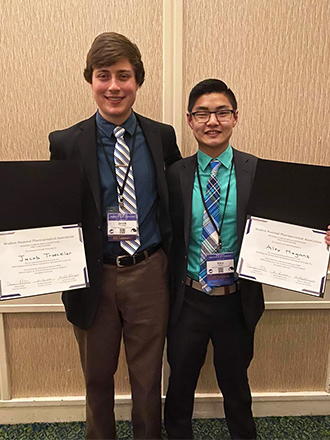

The rankings are determined by using data collected from College Navigator regarding tuition, as well as program information gleaned directly from each institution’s website. For more sizeable rankings, the methodology used to determine placement is based primarily on tuition. It also considers factors such as program flexibility, customization within the degree program both in content and format, and an overall “wow” factor that highlights each program’s unique offerings and sets it apart from the pack. For programs that have limited online availability, institutions are ranked based solely on tuition cost. A Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Pharmacy (SOP) student team achieved first place in the Student National Pharmaceutical Association’s (SNPhA) Regional Clinical Skills Competition. The duo edged out 35 other teams competing from the region’s 30 states during the 2020 SNPhA Regional Conference held Feb. 14-16 in Lexington, KY.

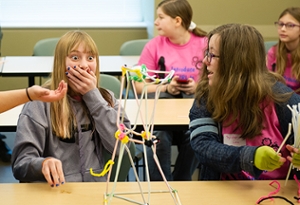

A Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Pharmacy (SOP) student team achieved first place in the Student National Pharmaceutical Association’s (SNPhA) Regional Clinical Skills Competition. The duo edged out 35 other teams competing from the region’s 30 states during the 2020 SNPhA Regional Conference held Feb. 14-16 in Lexington, KY. The Society of Women Engineers (SWE) at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville held its eighth annual “

The Society of Women Engineers (SWE) at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville held its eighth annual “ Professional women engineers and SIUE students were on site providing support and guidance to participants. Following the completion of each activity, the professional engineers and the SIUE engineering students offered analysis, and asked the participants probing questions about their projects.

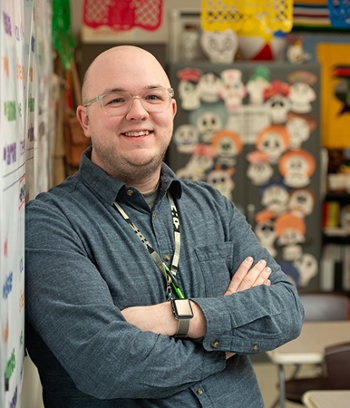

Professional women engineers and SIUE students were on site providing support and guidance to participants. Following the completion of each activity, the professional engineers and the SIUE engineering students offered analysis, and asked the participants probing questions about their projects. Southern Illinois University Edwardsville graduate student Caleb Romoser isn’t waiting until after graduation to implement his advanced degree training. He’s using his new knowledge in real-time to make a positive difference in an area school district by helping to combat racism.

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville graduate student Caleb Romoser isn’t waiting until after graduation to implement his advanced degree training. He’s using his new knowledge in real-time to make a positive difference in an area school district by helping to combat racism. From the pages of history to today’s headlines, the relationship between the African American community and the police has been an antagonistic one, according to Timothy Lewis, PhD, assistant professor in the Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Department of Political Science. Lewis, who specializes in identity politics, coordinated and moderated “Black and Blue: A Panel Discussion on Relational Policing in the African American Community.”

From the pages of history to today’s headlines, the relationship between the African American community and the police has been an antagonistic one, according to Timothy Lewis, PhD, assistant professor in the Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Department of Political Science. Lewis, who specializes in identity politics, coordinated and moderated “Black and Blue: A Panel Discussion on Relational Policing in the African American Community.”  “I have been a federal officer for 12 years, and during that time I have been stopped 14 times. I’ve been stopped three times while on duty and 11 times on my own time. I have only been stopped by white male police officers.”

“I have been a federal officer for 12 years, and during that time I have been stopped 14 times. I’ve been stopped three times while on duty and 11 times on my own time. I have only been stopped by white male police officers.”  The Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Nursing (SON) and John A. Logan College (

The Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Nursing (SON) and John A. Logan College ( The Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Engineering (SOE) celebrated outstanding students, faculty and alumni for their academic excellence, service and leadership during its 14th Annual Awards Banquet held Tuesday, Feb. 18 in the Morris University Center’s Meridian Ballroom.

The Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Engineering (SOE) celebrated outstanding students, faculty and alumni for their academic excellence, service and leadership during its 14th Annual Awards Banquet held Tuesday, Feb. 18 in the Morris University Center’s Meridian Ballroom. Awards were also presented to a researcher, adjunct instructor and faculty member for their exceptional performance and service. Additionally, the Computer Association of SIUE (CAOS) was named the Student Organization of the Year.

Awards were also presented to a researcher, adjunct instructor and faculty member for their exceptional performance and service. Additionally, the Computer Association of SIUE (CAOS) was named the Student Organization of the Year. Negative preconceived ideas, feelings of isolation and virtually no exposure to black scholars are struggles that black students face in college classrooms at predominantly white institutions (PWIs), according to Timothy Lewis, PhD, assistant professor in the Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Department of Political Science.

Negative preconceived ideas, feelings of isolation and virtually no exposure to black scholars are struggles that black students face in college classrooms at predominantly white institutions (PWIs), according to Timothy Lewis, PhD, assistant professor in the Southern Illinois University Edwardsville Department of Political Science.  “I’ve been in honors classes where I was asked, ‘How did you get in here?’” said Christen King, a senior, majoring in criminal justice and SIUE women’s basketball player. “I’ve also been told that I speak well. It’s hurtful.”

“I’ve been in honors classes where I was asked, ‘How did you get in here?’” said Christen King, a senior, majoring in criminal justice and SIUE women’s basketball player. “I’ve also been told that I speak well. It’s hurtful.”  “That isolation allows you to stay ignorant,” said Telisha Reinhardt, admissions and records officer in the Office of the Registrar. “I was in the military, and I served with people who had never seen black people before. While military is not a perfect institution, it forced people to look at your fellow sailor with respect, because they may be the one to save your life one day.”

“That isolation allows you to stay ignorant,” said Telisha Reinhardt, admissions and records officer in the Office of the Registrar. “I was in the military, and I served with people who had never seen black people before. While military is not a perfect institution, it forced people to look at your fellow sailor with respect, because they may be the one to save your life one day.”  The computer science field is rapidly growing, presenting boundless career opportunities. But, males greatly outnumber females in the industry. The Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Engineering Department of Computer Science (CS) wants to ensure females are a part of the field’s surging growth and success.

The computer science field is rapidly growing, presenting boundless career opportunities. But, males greatly outnumber females in the industry. The Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Engineering Department of Computer Science (CS) wants to ensure females are a part of the field’s surging growth and success. Medical pioneers from St. Louis Children’s Hospital’s Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Institute (CPCI) are collaborating with established clinicians and educators, and aspiring speech-language pathologists (SLP) at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville to offer high-caliber care for area children and adults.

Medical pioneers from St. Louis Children’s Hospital’s Cleft Palate and Craniofacial Institute (CPCI) are collaborating with established clinicians and educators, and aspiring speech-language pathologists (SLP) at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville to offer high-caliber care for area children and adults. Southern Illinois University Edwardsville’s Gireesh Gupchup, PharmD, director for university-community initiatives and professor of pharmacy, has been named 2020 auxiliary board chair for the Southwest Illinois Division of United Way of Greater St. Louis. He succeeds Jay Korte, director of client relations at The Korte Company, who has held the chair position since 2018.

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville’s Gireesh Gupchup, PharmD, director for university-community initiatives and professor of pharmacy, has been named 2020 auxiliary board chair for the Southwest Illinois Division of United Way of Greater St. Louis. He succeeds Jay Korte, director of client relations at The Korte Company, who has held the chair position since 2018. JewelRide, a client of the Illinois Small Business Development Center (SBDC) for the Metro East at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, has become a Medicaid approved provider, now offering their services to Medicaid recipients.

JewelRide, a client of the Illinois Small Business Development Center (SBDC) for the Metro East at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, has become a Medicaid approved provider, now offering their services to Medicaid recipients. Southern Illinois University Edwardsville’s Tiana Clark has earned the prestigious 2020 Kate Tufts Discovery Award for her book of poetry, “I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood.” The award is bestowed annually by Claremont Graduate University (CGU) to honor a first book by a poet of promise.

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville’s Tiana Clark has earned the prestigious 2020 Kate Tufts Discovery Award for her book of poetry, “I Can’t Talk About the Trees Without the Blood.” The award is bestowed annually by Claremont Graduate University (CGU) to honor a first book by a poet of promise.